Education for Sustainable Peace: an ongoing journey

Lia da Giau, April 2024

Building on my experience as student and researcher interested in peace literacy and sustainable development (SD), I will reflect on how education for sustainable development contributed to shaping my research on peace education at the Visualising Peace project.

Sustainable development, for how I came to understand it through my studies and in agreement with one of my most recent library entries, “is a concept in which social justice is upheld whilst people live within the carrying capacity of the planet. […] at its core it recognises the rights of all humans to have their needs met whilst respecting the rights of nature. It demands that we think to the future whilst learning from the past.” (White, King and Leask 2023).

To me, the link between peace education and global aspirations to sustainable development emerges clearly. Peace, as much as sustainable development, sits on premises and outcomes of global justice, and relies on collective responsibility to implement change. This is emphasised also in the UNESCO’s Recommendation on Education for Peace, Human Rights and Sustainable Development, which:

“acknowledges that education in all its forms and dimensions, in and out of schools, shapes how we see the world and treat others, and it can, and should, be a pathway to constructing lasting peace. The Recommendation logically links different thematic areas and issues, from digital technologies and climate change to gender issues and fundamental freedoms. It indicates that positive transformations are needed in all these domains because education cuts across all of them, being both impacted by all these factors and influencing them.”

UNESCO 2023

Eager to explore of the idea of ‘revolution’ in peace and conflict dynamics when I first joined the Visualising Peace team in 2022, through the years the thematic focus of my research has shifted towards an understanding of peacebuilding processes as quests for balance instead – balance between the aforementioned ‘domains’, but also in personal and global relationships with oneself, others, and the Earth system. The focus on relational aspects of peacebuilding is not new, and ideas of harmony, oneness and unity emerge in many philosophies (you can explore how the ideas discussed in this article relate to Stoic philosophy in our library, Withining et al. 2018), religions and sciences (e.g. ecology). A paradigm of relational interconnectedness in education tailors the learning experience to understanding the overlaps and diversity of ways to relate to the world, and in doing so ‘filling the gaps’ unaddressed by more compartmentalised views of education and the world in general. To me, this is where our approach to peace literacy at the VIP, inclusive of diverse voices and perspectives for long neglected in top-down approaches (e.g. youth participation), finds its relevance.

Sir Geoffrey Adams, former UK diplomat who joined the class as guest speaker in March 2024, mentioned how in decision-making ‘stability often trumps [positive] peace’. That explains how, sometimes, interventions to address a conflictual/unstable situation are de facto motivated less by the proposition of creating the conditions for sustainable peace and more by that of maintaining pre-existing stability – as the structural condition (the so-called ‘status quo’) which arguably favours trade, safety, and economic and human development. The rigid pursuit of stability feels to me hardly applicable to the patchwork of dynamic challenges characterising our transforming global system. On the contrary, a framing of peacebuilding oriented towards balance pushes for the recognition of points of equilibrium within motions of change. While revolution and stability appear as antithetic, my research this semester led me to visualise the potential for reconciliation between the striving for (social) change and balance. In her contribution to one of our lessons, prof. Rachel Kerr (War Crimes Research group, King’s College London) described reconciliation as crucial component of transitional justice, which is the dimension of social justice concerned with processes and measures implemented in societies undergoing transformation.

EDUCATION FOR SUSTAINABLE PEACE: TOWARDS BALANCED RELATIONSHIPS

The emphasis placed by the United Nations (UN) on “universality, indivisibility, interdependence and interrelatedness of all human rights” in their zero draft of the Pact for the Future informs an understanding of peace as balance between people’s human rights. However, reflecting on past and future trajectories of global governance in education and beyond, the pact partially acknowledges how top-down interventions have so far led to insufficient outcomes and perpetuated structural inequalities. These structural inequalities are framed as interlinked, making our international system particularly unstable by nature. It is in this context that relational indivisibility of humankind (and nature, within the Earth system) is presented as crucial for the “revitalisation” of global institutions, calling for “multilateral” solutions and begging the question of how education can equip students to develop those solutions. In this regard, the work of ecofeminist peace activist and educator Betty Reardon offers precious insights (Dale 2019, Dale and Reardon 2015). In terms of educating to tackle ‘multilateral solutions’, at the Visualising Peace project we have been trying to encourage conversations on root causes and established narratives of conflict as much as on ways to alter those narratives for positive change – adopting methodologies like the Root Narrative Theory introduced to us by the Narrative Transformation Lab at George Mason University during one of our seminars this past semester.

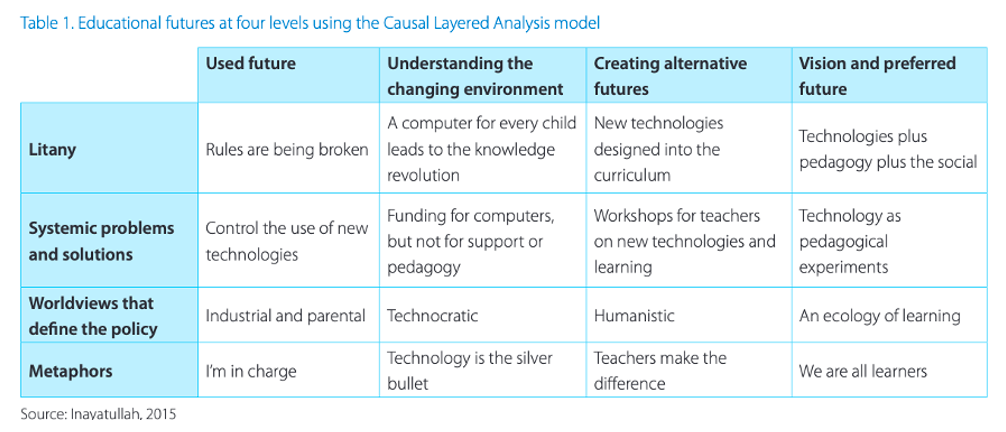

The importance of narratives emerged also in some of the resources I added to the Visualising Peace Library; White, King and Leask 2023, and Inayatullah 2020. The first source presents ‘stories of success’ about change as a source of hope in front of contemporary global challenges, and as something signalling that there is a fertile terrain for collective change to occur. Their use of the ‘stories of success’ to inspire further action shares similarities with how we hope for users to engage with the ‘pockets of peace’ showcased in our Museum of Peace. The second, similarly to the Root Narrative Theory approach, highlights the potential of narratives and metaphors to be accommodating or resistant to the change necessary to achieve a desired future. By “rethinking and relearning” their core narratives and metaphors, actors better connect to their purpose and directionality – which is shown to enable meaningful action for change. The new narratives and metaphors that results from this process makes it possible to have something to act on, and to deal with tensions between present and future needs and wants. Unlearning practices and narratives that prevent change from happening, together with the mapping and pursuing of alternative futures, ultimately allows us to identify the type of change needed to alter the status quo – be it marginal, reformist, or radical. They give practical examples of what this work on narratives and metaphors looks like in education:

If the resistance to change of established (social) structures is increasing the instability of our system, the field of education is not an exception. Despite investment in “co-creating educational futures” (Inayatullah 2020), as we ourselves have aimed to do through our work on the Visualising Peace project, the question of how to accommodate emerging visions is limited in scope due to institutionalised views of education still holding a strong ground, and curricula falling short in covering appropriately contemporary issues (see also Whiting et al., 2018).

It is worth pin-pointing emerging disruptions and trends in the field, which educators should account for when considering alternatives to current approaches:

Commission on the Futures of Education 2021, Inayatullah 2020, White, King and Leask 2023

- Students as co-producers of knowledge: pedagogies and practices led by principles of cooperation, collaboration and solidarity, redefinition of the teacher/learner dynamics, away from hierarchies and towards creating democratic, dialogical relationship of mutual exchange.

- Expanding boundaries of the classroom: merging between national/global approaches, learning occurs during one’s whole life and in different sociocultural settings.

- Artificial Intelligence, technology and shift of the role of teacher from lecturer to “facilitator and knowledge navigator”.

- Fast-paced global change: knowledge and skills acquired in schools are increasingly irrelevant to meet real-world needs.

Co-production of knowledge is integral to how we understand Peace education at the Visualising Peace project. Similarly, the kaleidoscopic personal-local-global scope of education is something we have tried to incorporate in our approach. The need for more digital literacy as a means to mitigate online violence emerged often during a series of responsible debate events organised by fellow Visualising Peace members on the theme of social media and peacebuilding, and also in one team member’s research into AI; and the idea of working on narratives to promote peacebuilding in theory and practice is at the core of our mission. The changing nature of the world has made current education systems inadequate to respond to the needs of the present, and most sources I engaged with in my research highlight how curricula should integrate ecological, intercultural and interdisciplinary learning, placing emphasis on synergic effort of learning and applying knowledge at once to shape the world within our circles of influence. What underpins this approach is a belief that anyone can become an agent of positive change in their locality with a ripple down effect, if they are given appropriate learning opportunities to do so.

The above approach aligns with critical theories stemming from the work of Brazilian popular educator Paulo Freire – for example the ecopedagogies presented in Whiting et al 2018 in our library. We too agree with Freire and others in that education can shape society through processes of deconstruction of injustices and reconstruction of relationships. This well connects with narrative-based approaches for social change explored previously, emphasising the importance of unlearning practices and narratives that prevent change from happening by mapping and pursuing preferred futures, adding to that an ecological dimension in line with approaches to education for sustainable development.

EDUCATION FOR SUSTAINABLE PEACE: WHAT MORE CAN BE DONE

My learning journey on peace education this semester has shed new light on a formal commitment of local (Scottish Government, with their Action Plan on Learning for Sustainability ) and global institutions (UN/UNESCO documents) to adopt more participatory and integrated approaches to education for peace and sustainable development. Yet, in the categorisation of policy areas within the UN Pact for the future, international peace is presented in relation to notions of ‘security’, while sustainable development is paired with ‘finance’. The relationship between peace and SD only emerges at p. 8, with the recognition of “the interdependence of international peace and security, sustainable development and human rights.”, where SD is presented as a means to tackle “underlying drivers and enablers of violence and insecurity and the consequences thereof”.

However, the term ‘sustainable peace’ is too often understood in its temporal dimension (‘peace that lasts in time’), overlooking the social weight that the adjective ‘sustainable’ carries with it. What is sustainable is socially just, and as such begs for transformation of unjust systems. In SD, extractive dynamics of discrimination, oppression, exploitation between people and/or towards nature are a crucial aspect in the analysis of what makes a system unjust. As such, debates on sustainable peace cannot transcend discussions of post-capitalist and post-colonial framings.

Despite the recognition of youth, gender and minorities’ inclusivity in top-down peacebuilding, these still fail to address explicitly the intersectional nature of root problems and solutions which critical approaches are most concerned with nowadays – and that peace activists and educators like Freire and Reardon have been promoting for some time, by bringing into the realm of recognition women and indigenous/local people’s worldviews. To better understand what change of perspective might be needed here, imagine your ceiling was leaking in different spots (the multiple interlinked challenges people need to be prepared to tackle) every time it rained; wouldn’t it make more sense to fix the roof rather than keep placing buckets under the individual leakages?

Now, in both the field of sustainable development and peace studies there are varying opinions on how the ‘roof’ of our global system should be fixed, and – more problematically – on how it broke in the first place (arguably, as I could draw from my recent reseach, the blame could be put on a deleterious synergy between legacies of colonialism, patriarchy and neoliberalism…but this discussion would need more space than this reflection allows!). The potential for SD to contribute to peace education and peacebuilding in general, from a conceptual and practical point of view, is still largely untapped. Yet, the current climate of global institutional and social change suggests that there might be space for sustainable and peaceful transitions to be experimented and enacted in collaboration.

LIBRARY ENTRIES

United Nations. Pact for the future: zero draft, January 26, 2024. https://www.un.org/en/summit-of-the-future/pact-for-the-future-zero-draft.

The ‘Pact for the future’ was developed as part of the background documentation informing the upcoming Summit of the Future, hosted by the UN in September 2024. As such, this entry is a useful resource on emerging themes in the international fora; it could be an interesting read for those looking to become more literate and aware as ‘global citizens’ – a crucial component of peace education. It also provides a good framework for understanding notions of global crises and systemic (socioeconomic, environmental, technological, and political transformations). The report frames the present as characterised “potentially catastrophic and existential risks” but also as a “moment of opportunity”. The Pact makes if evident how global challenges do not occur in isolation, pushing us to visualise current political, economic, technical and socioenvironmental changes as experimental spaces for the implementation of more intergenerational and collaborative approaches to global governance – which would arguably contribute to peace on multiple levels.

This source is particularly relevant not for the evidence it presents but for the discursive trajectory of change it proposes. Foreseeing similar emergencies which different communities worldwide are expected to face in the years to come, the Pact encourages multilateral action on a local to global level. The main areas of change and action explored in the Pact are:

- Sustainable development and financing for development,

- International peace and security,

- Science, technology and innovation in digital cooperation

- Youth and future generations

To critically contextualise the source, one could explore more in-depth debates around the adoption of institutional (top-down) VS grassroots (bottom-up) approaches in the promotion of peace and/or sustainable development. We emphasise the necessity of constantly evaluating whether interventions and narratives promoted by global/transnational institutions (e.g. the UN, but it also applies to other realities, NGOs, and multinational corporations) pertinently involve local communities – in an attempt not to reproduce (neo)colonial dynamics of for-profit exploitation and erasure of cultural diversity.

White, Rehema M., Betsy King, and Kirsten Leask. “Catalysing a Movement for Change through Learning for Sustainability: Gathering for Inspiration.” Learning for Sustainability Scotland, 2023. https://learningforsustainabilityscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Catalysing-a-movement-for-change-FINAL.pdf.

The report is published by Learning for Sustainability Scotland, Scotland’s UN University-recognised Regional Centre of Expertise in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). It presents an overview of Scotland’s changing educational landscape, in the context of ongoing curriculum reforms to introduce learning for sustainability in all 3-18 places of education in the country. This follows the publication in June 2023 of the Action Plan on Learning for Sustainability by the Scottish Government – which key themes and actions are presented in the report.

The report is a summary of the discussions emerged during a “creative yet critical gathering” held by Learning for Sustainability Scotland, in August 2023. The gathering brought together policymakers and agencies, academics and education practitioners, and NGOs. After exploring some success stories and challenges characterising movements for change in education, the focus moved on implementation. Participants engaged in exercises to co-design a movement for learning for sustainability in Scotland, and responses/reflection from those workshops are presented and contextualised in the report. The last section, presenting ‘Perspectives on the ‘Movement for Change’, is particularly effective in giving a hopeful view that understands change as a process in continuity. It includes reflections from participants from different walks of life, giving insights on their initial reflections and their understanding – developed through the activities – of how to make change happen.

Exploring processes, limitations, and amplifying factors for change, this source offers precious recommendations that could be progressively applied on a wider scale beyond education – not only in the transition towards sustainable development, but in the various movements for change that interact in the arena of peace studies and practices.

Inayatullah, Sohail. “Co-Creating Educational Futures: Contradictions between the Emerging Future and the Walled Past.” unesdoc.unesco.org, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373581?posInSet=20&queryId=00615579-6ed0-447a-b384-e7069524f683.

As part of the periodical series of UNESCO documents grouped under the label of Education, research and foresight: working papers, this source helps stretching our understanding of peace education in the field of futures studies. Futures thinking intervention processes are examined in the historical and present context of changing educational and global systems. Global and educational transformations here go hand-in-hand, connecting to neohumanist notions of intellectual liberation; the role of education is explored beyond its instrumental dimension of preparing individuals for the job market, and towards acknowledging it as way to acquire “learning tools about self, the world, and the future”. It offers international examples (Australia, Malaysia, Norway, China) of how future thinking can be used to develop alternative narratives which support transformative processes in education. This process entails letting go of outdated/inadequate approaches to make space for other plausible and preferred ones that bring benefits in both short- and long-term scenarios. Another important contribution that the paper makes is to highlight factors that tend to slow down or prevent change: amongst these, rigidity of educational systems on a local to global level, grassroots/institutional resistance to transformative action, inadequacies in communicating the present relevance of future-oriented solutions, and uncertainty around how to ensure innovation does not lead to exclusion of surpassed practices/institutions. An approach to futures literacy that integrates several success factors from other foresight interventions within and beyond the educational field is then proposed as a ‘learning journey’ that educators/institutions can embark on. Future literacy entails adopting systems thinking to create scenarios accounting for duality of risk-opportunities that contemporary global challenges present. While the source has been linked more directly to discourses around peace education, the insights it provides are applicable to other peacebuilding approaches and can inform a wider, cross-sectoral transition towards peaceful societies.

Whiting, Kai, Leonidas Konstantakos, Greg Misiaszek, Edward Simpson, and Luis Carmona. “Education for the Sustainable Global Citizen: What Can We Learn from Stoic Philosophy and Freirean Environmental Pedagogies?” Education Sciences, Education for Social Transformation: Initiatives and Challenges in the Contexts of Globalization and the Sustainable Development Goals, 8, no. 4 (November 19, 2018): 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040204.

The article suggests a pedagogical and theoretical framework that could inform the implementation of the Global Education First Initiative (GEFI), promoted by the United Nations to increase access and quality of global citizenship education. The article proposes interesting links between the values attributed to education in ancient philosophy and contemporary debates around education for sustainable development. It stresses how both Stoicism and Freirean-influenced environmental pedagogies respond to calls for updated educational systems which shape rather than replicate the status quo. It explores idea of virtue and education in an evolving context, considering ancient Stoic perspectives alongside that of more contemporary philosophies and pedagogies, in particular ecopedagogies inspired by the work of Brazilian philosopher and educator Paulo Freire. By linking global citizenship education to education for sustainable development (ESD), the authors argue that Stoic cosmopolitanism and virtue education, together with Freirean-inspired ecopedagogies’ focus on supporting individuals’ development as impactful agents who can modify unjust socio-environmental dynamics, could be synergic approaches in supporting a transition to sustainable development. The relevance of this reading for peace studies lies in the attention they place on notions of global citizenship as means for social transformation – where ‘global citizenship’ is a “democratic facet of identity”, a kaleidoscope inclusive of multiple national and cultural identities. The Global dimension of citizenship (GEFI’s third pillar) is important because if ‘global challenges require global solutions’ people need to learn – not to be taught, as no one knows how to do it – to think in the global scale and about the wider common good too. The consideration of ecological approaches could also help expanding the scope of peace studies. A further reflection on the overlaps between peace and sustainable development is encouraged: how can we integrate analyses of human-nature relationships – characterised by conflict/harmony according to historical, personal and cultural factors – in the study of intra/interpersonal, local and global dynamics?